Karate is full of myths. Origins, connections to past traditions, mysterious teachers, hidden techniques, the list goes on. This isn’t surprising, in fact it is in keeping with the arts related to it, both in Japan and China. Sometimes, however, the myths can take on a little too much historical weight. That is certainly true in the Chinese arts, where things like the Southern Shaolin Temple, which in all likelihood never existed, and the legends surrounding its destruction and the diaspora of its surviving monks form the basis of the foundation myths of a number of Southern Chinese arts.

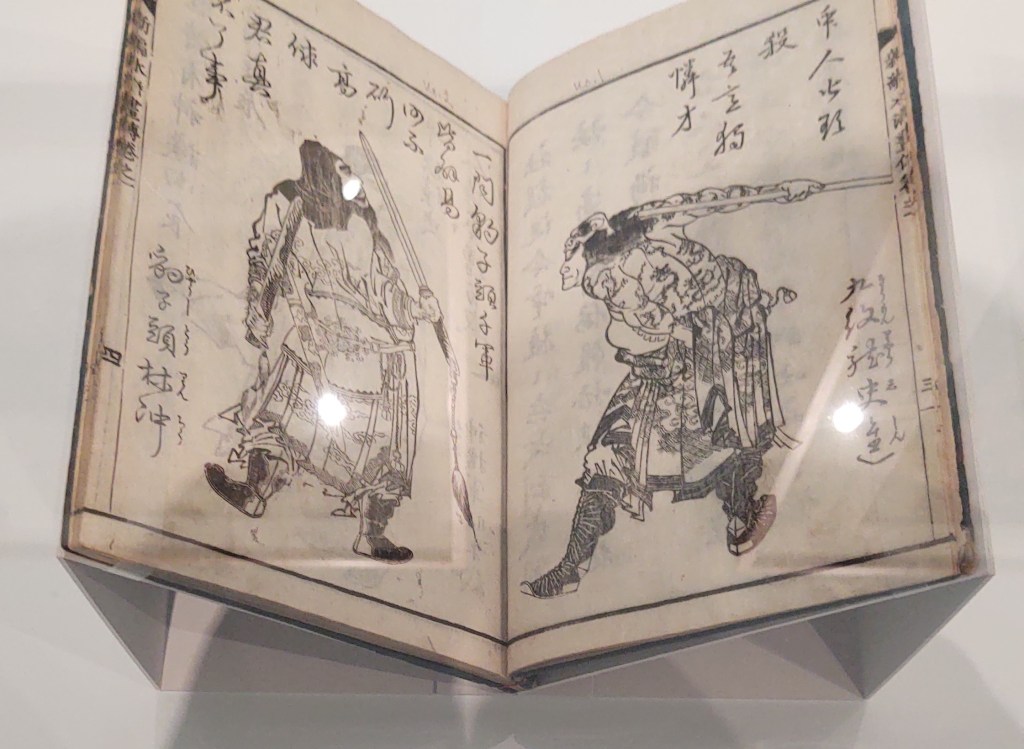

These legends seem, when scholars examine them, to be based at least in part on the stories told in The Water Margin, also called Outlaws of the Marsh, or All Men Are Brothers. This novel, which can be dated to at least 1524, is a treasure trove of martial arts tropes, as well as being quite a fun read. It has everything: monks fleeing burnt temples, masters hiding from the government, secret symbols and hidden training, mystical and magical martial skills, numerology, and so on.

Many of these tropes are also seen in the stories around karate in Okinawa. Mysterious teachers, hidden techniques, fighting back against an oppressive government, hidden meaning in the names of kata, these sound familiar, no? These go along with the stories of direct transmission from a mysterious Chinese teacher and secret or ancient Chinese knowledge. A lot of Chinese stuff, really, for an island more directly influenced by Japanese culture and political hegemony. A little background in Okinawan culture makes at least some of the reasons for this emphasis on Chinese knowledge obvious. There is an immense amount of cultural capital to be gained in traditional Okinawan culture through connection to Chinese knowledge or learning. More than from Japanese, regardless of the actual historical weight of the two.

When looking for the connections to the Chinese cultural impact on the Okinawan martial arts however, the emphasis is usually on trade, or the sapposhi, the Ryukyukan or Kumemura; on contact with the martial arts directly. But questions remain. Where did the founders learn their arts? Why are their teachers unknown? What exactly was Chinese and what Okinawan? And the stories also seem, familiar? Fleeing conscription in Okinawa or leaving on a quest for martial knowledge, becoming a disciple of a local master after helping him or his family, learning deeply and in secret, being the best student even if you were an outcast of some sort , fleeing having accidentally killed someone in China. Good stuff, if rather unoriginal. But while these stories are occasionally examined, looking at some of the larger Chinese cultural impact on the Okinawan martial arts is ofttimes ignored. How did music, the classics, or dance impact those learning martial arts? And what impact did literature or legend have?

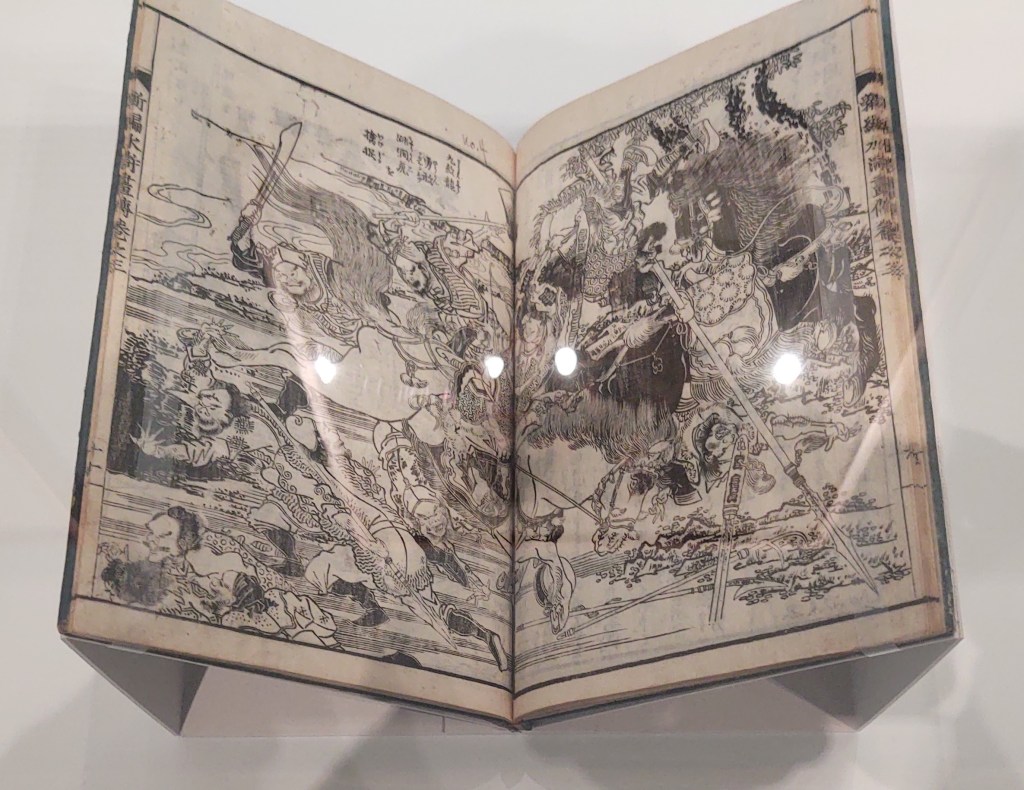

This last occurred to me most recently when I was visiting the Museum of Fine Arts here in Boston a few months back. Amusingly enough, I was in the company of one of my teachers, a senior in the Jigen Ryu from Kagoshima who was visiting. He wanted to see an Ukiyo e exhibit that was on. He was somewhat amused that the MFA has such a huge collection, known in Japan as well as here for being one of the best, and it was indeed a wonderful exhibit. Amongst the many works of art, the one that really jumped out at me was this: an 1830s reprint of an 1805 translation of The Water Margin illustrated by Hokusai. This was, at the time, a huge success and inspired a “Water Margin” craze. An 1827 reprint with art by Kuniyoshi jumpstarted his career and inspired a nationwide craze for whole body multi-color tattoos (as well as inspiring the reprint of the 1805 printing that had inspired Kuniyoshi). I hadn’t realized how popular, and persistent this book was in Japan. Somehow, I’d segregated the Chinese and Japanese cultural spheres, while in reality they merge a great deal.

As I said, this work had a huge impact on the founding myths of many of the southern arts. These arts in turn had some influence on the development of karate as we know it today. These martial arts cannot be separated from the legends that surround them (nor would I want to!). But in part because of the strength of these stories their actual history is often hard to discover. Powerful stuff indeed. And in looking at the influence of Chinese culture on the Okinawan martial arts it might behoove us to think a little more holistically. If we think about these stories as coming from multiple sources, filtered through multiple cultures, it might be another window into their influence. In reality it isn’t just from whatever direct transmission of technique or information that happened that this influence is felt.

And therefore it isn’t just from Chinese sources that Chinese culture can enter the arts. In this case, a set of foundational stories that was hugely influential in China, and to the arts that then influenced the Okinawan arts, was also very popular in translation, with editions being published periodically and remaining popular through the Edo (from at least 1757 on) and Meiji periods. These would be known to any Okinawan martial artist who could read, and most likely, since they were so popular, even to those who couldn’t. So they would be part of the background of the art from both ends, as it were. Both through the direct transmission from Chinese sources, who would certainly have been familiar with the tales (and likely practiced arts that incorporated them into their own myths) and from the popular culture around the Okinawans.

So what Chinese influence then? Not just technique, but also myth and story. A multi variate influence. Happening at different times and through different media. Coming from variant cultural loci, and with accompanying variant levels of cultural capital, but regardless thereby being somewhat self-reinforcing. And much like the Chinese before them, it seems like not too much of a stretch to see the Okinawans also incorporating these stories into their own, particularly since they were getting them from all sides, as it were. Perhaps unconsciously, perhaps on purpose, but that is how myth and fact get intermingled. When, as humans do, we take what we are given and make ourselves the main characters of our own story.