A little while ago I posted a short piece on power generation. It came out of some thinking and training I have been doing moving back and forth between the “engines” of Goju, Feeding Crane, and Matayoshi lineage kobudo. In it I included a pretty standard power development method, rotation. However, I realized I had presented it incorrectly. I used the standard “body rotates around the spine” phraseology. But one of my students pointed out that I don’t actually teach rotation that way, at least in Goju or kobudo, and talking about it that way is essentially lazy, which makes it much harder to examine what we are doing.

It is difficult in text to describe some of this stuff, but I’ll give it a go.

First, the spine is rarely the point you rotate around, or perhaps more properly, from. Certainly you can, and certainly we do (more often in Feeding Crane, but I digress). But most of the time rotating around the spine means that ½ or so of your energy is going away from the direction you are trying to send power. That isn’t really very efficient, is it?

Let’s take a very simple example, a standard gyaku tsuki, like in geki sai. The rear leg pushes the rear hip. Connection with the lats, back, and abdominals ties the shoulder to the hip; through this set of connections, the “power chain”, the leg pushes the shoulder and from there the arm and finally hand. That rotation- the leg driving the shoulder- is what I am referring to. This is often described as the upper body rotating with the spine as the center axis. However, is it? If I look at the rotation that way, that would mean that the opposite hip moves backward, away from the direction the punch is moving. As I was taught, and as I teach, that is not the case.

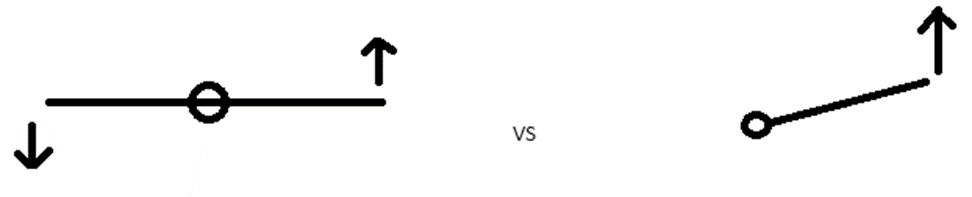

Instead, that hip becomes the point of rotation, the pivot point. Think of the torso like a door, the “frame” we often talk about. If the pivot is in the center of the door, representing the spine, when you push on one side the door spins and as that side goes forward the other goes back. Now instead think about the door with the hinge on one side. The door opens with the hinge as the pivot point. This hinge is the opposite hip.

Instead of always rotating around the spine we can choose our pivot point. In this example it is the opposite hip but it can be other places. Try it. It might come very naturally, or it might feel really weird. The movement goal for a basic gyaku tsuki would be to limit the rearward motion of the opposite hip while allowing for full extension of the rear leg and good penetration with the punch, all without twisting the torso (breaking the frame). For Goju folks, this is essentially one aspect of sanchin, where we punch without pulling the opposite hand/shoulder/hip away from the front….

The power generation goal is to dump all the momentum of the punch, not just ½ of it, into the target. That includes the mass behind it, not just ½ the mass. This is why the knee release on the front leg is important.

Try the punch again, slowly. If you don’t release your knee it is, for me anyway, harder to prevent that opposite (front) hip from moving backwards as the rear leg pushes, at least without adding a lot of tension to that leg to stabilize it or lock it in place. But if you release the front knee it allows that hip to remain open, and perhaps even move a little bit forward and/or down. I find this makes it easier for that hip to be used as the pivot point. We call this “emptying” the leg. In essence, when you hit that leg could just as easily be lifted off the ground for a split second, leaving that side totally unsupported. Empty. Then all the weight along with the pushing force is transmitted in a line from the rear heel to the end of the punch. (The same applies for a huge variety of other attacks, or motions in various planes, I’m just trying to stay focused on one example at the movement.)

I often see people pushing with that opposite leg, straightening the knee slightly and pushing the hip back. This can create a very snappy pivot around the spine, moving off a fixed and equally supported base. This can feel good, fast and powerful, as your whole body is engaging in the movement and you are well supported so don’t feel unbalanced. I don’t think it allows for a “unified body” energy transfer, with the entire weight of the frame behind the technique, but of course other results may vary.

Anyway, thinking about rotation a little differently might be helpful in your practice. Or it might not. But examining this part of your mechanics is likely to be helpful if you want to work on connecting the various elements of your practice to the roots of your system and the movement theories behind it. I don’t know about you, but to me this approach more closely resembles the fundamentals of the Goju engine, and its basic expressions in Sanchin, among other things.

Bingo! Thank you for this. I’ve been trying to explain this to people for years using the same door example. I won’t go into detail (I know you know already) but very simplified I kind of explain the difference in a door swing. Well….as you just did but not as good as you did. Picture the doorknob as a fist. If I swing the door at you the doorknob hits you with the weight of the door behind it and the hinge side is the pivot point. Now. Picture the doorknob being on the hinge side. Swing the door all you want the doorknob (fist) does nothing. My explanation always had more to do with explaining getting bodyweight into a punch and started from a debate I was having with a training partner over a particular punch. We disagreed on the pivot foot. I told him his way had the fist (doorknob) on the hinge side. At the time we were discussing a boxers left hook with the lead hand ( left foot forward stance). We disagreed on which foot was the pivot point. The door explains it in my opinion.

Thanks again. Good explanation.

LikeLike

Thomas, thank you and glad you enjoyed the piece.

LikeLike