I’ve written a couple of posts, here and here among others, about what I think actual research into the Japanese and Chinese martial arts entails. Things like cultural, linguistic, historical, and contextual background are not “added flavor”, or a nice bonus, but I believe absolutely necessary to do anything that can realistically be called “research”, as opposed to opinion, narrative, training methodology, or possibly ethnography.

I don’t usually do book reviews. However, I recently read Unravelling the Cords, a translation and annotation of some documents relating to the Taisha Ryu. It is a wonderful read, well worth the while, particularly if you have any interest in Japanese sword arts. Indeed, it is both readable and a perfect example of what research into written material on the classical arts should be. It creates context for the text in a variety of ways, all necessary for understanding it. They include: the oral instructions and annotations passed down generation by generation to the current lineage holders, the physical practice as it relates to the text, the history leading up to the text’s creation, the previous and surrounding texts that influenced it, the Buddhist, Daoist, and Confucian thought that runs through the text, the cultural and social surroundings of the author at the time of the text’s writing, and the linguistics inherent in an archaic text like these.

The translation is accompanied by extensive footnotes explaining elements of these things as they pertain to various passages, and to the text as a whole, as well as by some sections dedicated to the background of the text. The translation, annotations, and accompanying notes and background all serve to make the text understandable to the reader in a way it simply would not be otherwise. They also make a very important point about work like this: the text is not only very difficult to understand as a non-native speaker of Japanese, but it is pretty much incomprehensible to a modern native speaker, and moreover would have been mostly incomprehensible to a native speaker of the time who did not have the necessary education, covering a specific set of Chinese and Japanese classic literature and philosophy texts in particular. It was written for a particular audience at a particular time. Understanding it requires having the necessary background in the history, culture, language, philosophy, and martial art that the text is based in. Trying to translate it with a dictionary simply won’t do.

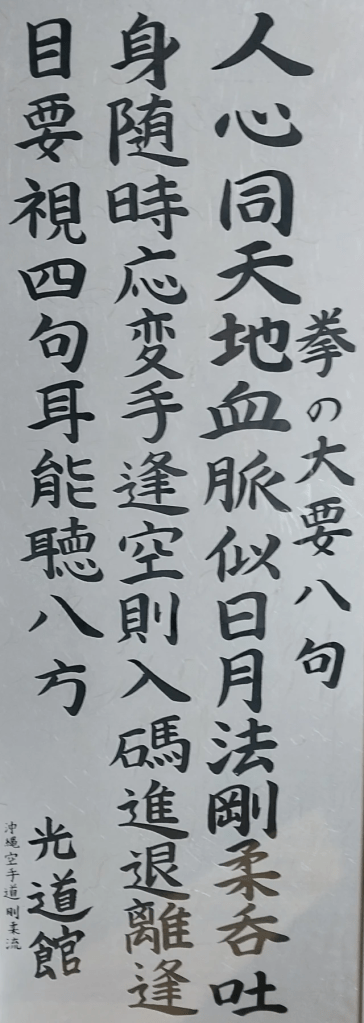

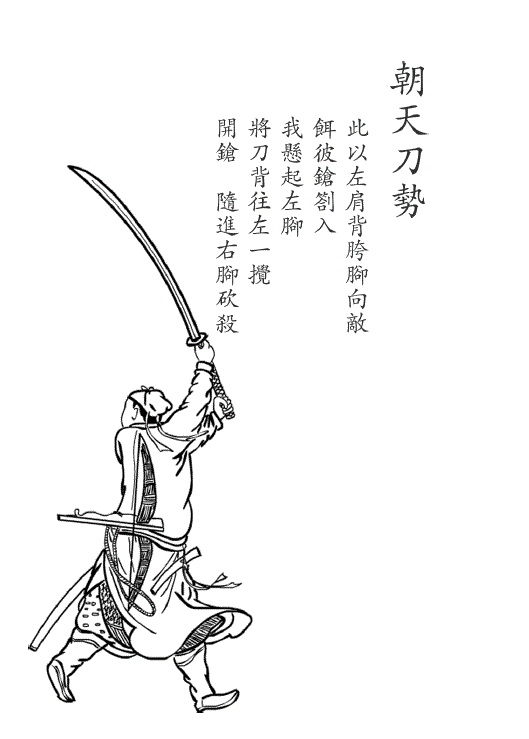

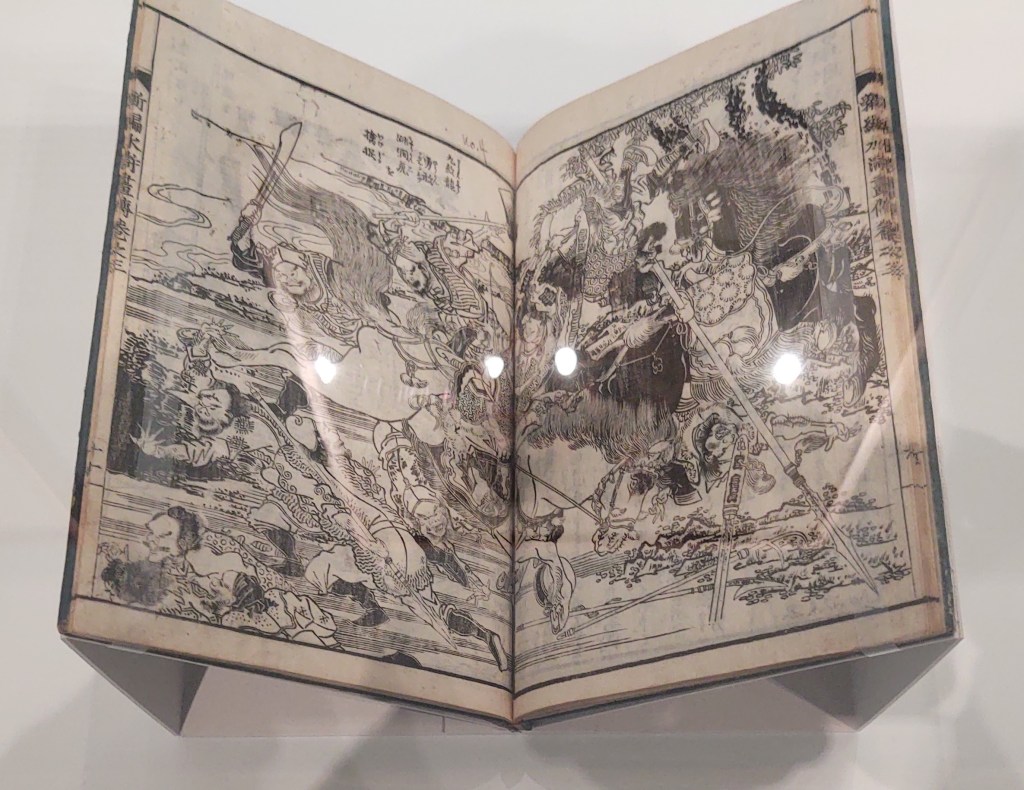

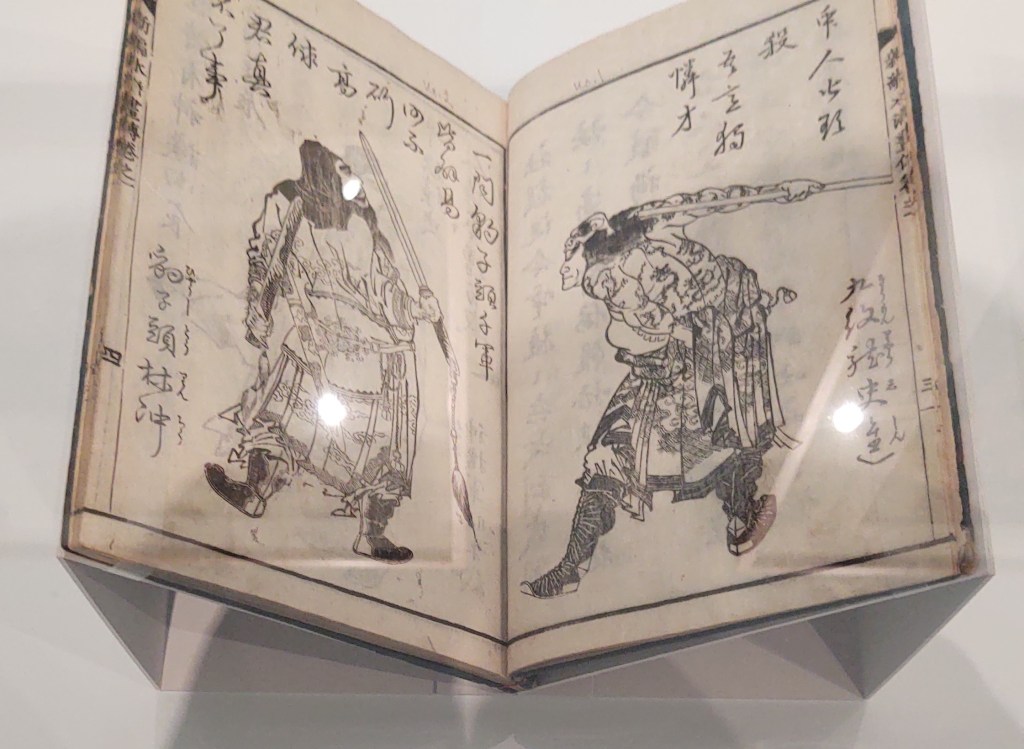

Stuff like this is hard. It requires a huge amount of work, mostly involving years of prior education, as you need to have the context available to you when you start and without it likely won’t even know what you are missing. I am reminded of this right now as I am working on a much less esoteric translation, the book on Feeding Crane Boxing my teacher’s father published in Japanese in the 80s. It is much simpler, written as an introductory text in modern Japanese. But it is challenging for me, as my Japanese is not what I would consider fluent. There are also sections of classical Chinese, primarily excerpts from the Bronze Man Book the family holds, that would be difficult or incomprehensible for a native Japanese reader. They would be very challenging to a native Chinese speaker today. Most of these are accompanied by Japanese translations and/or commentary, which is helpful. But it is a reminder that texts like these can, on the surface, appear simple but often are not. At times there have been specific terms and references that only my experience with Feeding Crane’s terminology, training in Feeding Crane, and discussions about the art and it’s principles, history, and theory with Liu sifu have prevented me from mis-translating.

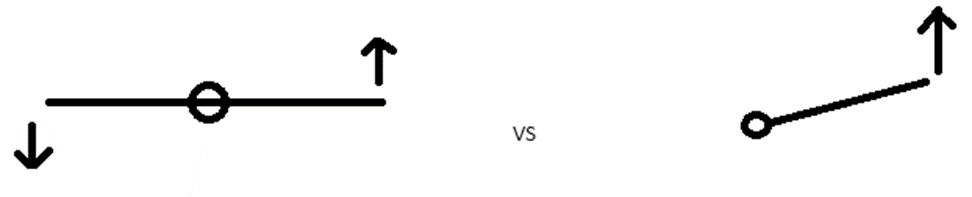

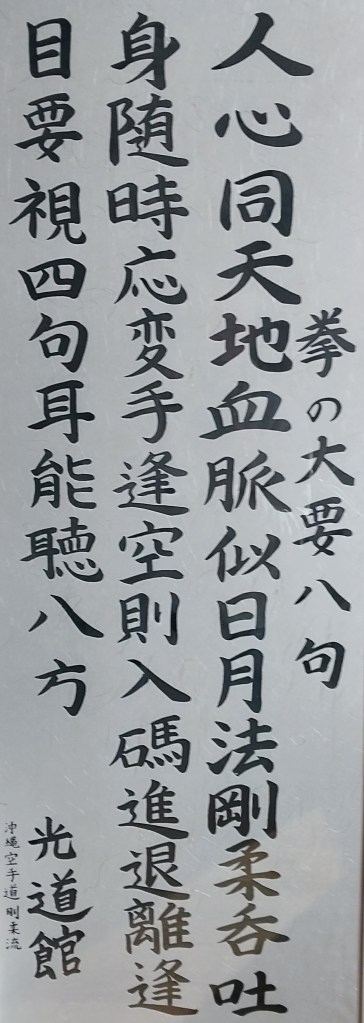

Not surprisingly, some of the Chinese poetry about training reminds me of the Bubishi, in particular the Kenpo Hakku. These are also quite difficult to translate in any meaningful way, and the context they were written in has a huge impact on their meaning. I talked about how I think context affects one line here and here, but while I like my perspective on that line better than the extant approach, I can’t really say I am right.

I can say however, that work like Unraveling the Cords is what I believe these arts need. There is a great deal of high quality existing work on the classical arts in Japanese and Chinese, but good translations of any of it are rare. There is also a great deal of extant older material- quanpu, densho, and so on- that if translated would expand the current body of information outside their native languages and in my opinion help push understanding of these older arts forward. But translating any of it is a lot of work, and there is a fairly limited audience for it, making the time and effort required a labor of love; one is very unlikely to be able to cover even a portion of the time and expense needed to do this kind of work from the work itself.

In any case, if you get a chance, read the book. You might also look at the work of the few other folks who are working to bring good translations to a larger audience, people in the karate world like Joe Swift, Mario McKenna, Patrick McCarthy, or Andreas Quast. I know less about the literature in the Chinese arts but Russ Smith’s Taizu translation, Kennedy and Guo’s book on training manuals, and a few others are excellent, and people like William Scott Wilson have done some really good translations of Japanese texts. It feels like more of this is happening these days, as the community of Westerners with both the scholarly and martial backgrounds necessary grows. I certainly hope so! But meanwhile take a look past the “how to”, “my story”, or “my teacher is great” books. Some of those are excellent, and can be helpful or informative to your practice. However, some of these older texts now seeing the light of day are fascinating, and you might be surprised at what they hold.